Every year, the folks at MassMutual Life Insurance get together for “Data Days for Good”, where team members work to help a local agency or organization with a data science project. Through a research partnership between the University of Vermont Complex Systems Center and MassMutual, I learned about the Data Days for Good initiative, and in the spirit of that event, I turned a data artist’s eye toward our state’s evolving compost ecosystem.

As a gardener, I know the benefits of composting food scraps for improving soil quality and plant nutrition. What I didn’t know: there is a real cost to not composting. I had always assumed that food that didn’t make it into a compost pile would simply decompose in a landfill, but that’s not the case. Food that would decompose in a matter of weeks in a compost pile can take years to decompose in a landfill, taking up space and releasing methane into the atmosphere. Take carrots for example: In a backyard compost pile, they will be unrecognizable in just 9 weeks:

| 0 weeks | 4 weeks | 9 weeks |

|

|

|

In a landfill, because there are no decomposers in this anaerobic environment to digest the material, carrots that have spent nine years sitting under trash still look like this:

Many thanks to Lauren Layn at Green Mountain Compost for these fascinating photos, and for teaching me a whole lot more about compost in our great green state.

There is only one landfill in Vermont. It’s located in Coventry, just south of the Canadian border, and last year Casella Waste Management processed around 420,000 tons of waste there from across the state. The landfill is beginning to reach capacity, and while there are discussions taking place to address where future landfill materials should go, there is a more immediate solution: decreasing the amount of recyclable and compostable materials that end up there in the first place.

A 2012 study from the Department of Environmental Conservation found that 28% of the state’s municipal solid waste was organics. Paper, plastic, and glass comprised another 35% of what was being sent to the landfill. This data was part of the impetus for Act 148, the Universal Recycling Law, instated in 2012.

Meredith Niles is an assistant professor and faculty here at the University of Vermont, in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences’ Department of Nutrition and Life Sciences. Dr. Niles co-authored a paper this year on the “Relationship between food waste, diet quality, and environmental sustainability”. Meredith explains, “Our data suggest that the average person in the United States wastes about a pound of food per day”. That totals about one third of all calories available for consumption in the United States. The environmental impact of all that food waste is devastating: “The agricultural sector has been largely overlooked as both a source of [greenhouse gas emissions] and a potential tool for mitigation”, Dr. Niles explains here.

With the enactment of Act 148, Vermont became the first state to ban all food scraps from landfills. Setting a precedent doesn’t come without some logistical challenges, though. Like many of the systems we study here, this one is complex. Lawmakers in Vermont recognized this fact, and created a timeline to gradually phase out food scraps from landfill streams, beginning with large-scale commercial waste generators in 2014 and expanding the same requirements to households in 2020:

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2020 |

| Food scrap generators of 2 tons/week must divert material to any certified facility within 20 miles | Food scrap generators of 1 ton/week must divert material to any certified facility within 20 miles | Food scrap generators of 1/2 ton/week must divert material to any certified facility within 20 miles | Food scrap generators of 1/3 ton/week must divert material to any certified facility within 20 miles | Food scraps are banned from the landfill and haulers must offer food scrap collection |

| Transfer stations / bag-drop haulers must accept leaf and yard debris seasonally | Leaf, yard, and clean wood debris are banned from the landfill | Transfer stations / bag-drop haulers must accept food scraps |

via the Act 148 timeline, available here.

For curious folks in Vermont, the Agency of Natural Resources (ANR) has a fantastic “Open Data Portal” where you can find data sets about everything from fisheries and geology to waste facilities and food scrap generators. Using this data, I was able to start making sense of just how much food waste we produce as a state. Granted, a lot of these values are imputations from self-reporting and estimates based off categories like facility type (restaurant, school, hospital) and metrics (number of seats, students, beds), but the ANR put a tremendous amount of work into cataloging and making a best guess at what the actual food waste output is for over 5,000 companies and institutions across the state. When we put these places on a map, we see food scrap generation clustering around population centers and major roadways:

(Mouse over the canvas and scroll, or use the ‘+’ and ‘-’ buttons, to zoom. Click and drag to pan. Click on points to learn more.)

A first glance at the data shows that our distribution (the number of places generating food scraps across different categories of volume) skews very far to the left: many places produce a small amount of tonnage per week, while just a small handful generate a tremendous amount of food waste every week.

Actually, if we hover over the very tail end of our histogram, we’ll see that there is just one place producing a whopping 288 tons of food scraps every week. Along with maple syrup and beer, Vermont is known for its cheese, so it’s no surprise that our outlier, the state’s largest producer of food waste, is the Cabot farm in Middlebury, Vermont. As it turns out, their food waste goes right down the street to Foster Brothers Farm, where owner Bob Foster (who is also Chair of UVM’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Board of Advisors) has partnered with local green energy innovator AgriLab Technologies to create a thermal power system that uses the heat of decomposing waste to speed compost production and generate energy (read more about their story and others from Seven Days here). Their compost, “Moo Doo”, is sold to gardeners all over New England.

People are often surprised by how much heat large compost piles generate. From the photo below, taken during a visit to Green Mountain Compost here in Chittenden County, industrial-scale compost piles are required to reach at least 131°F, so it’s no wonder that folks around here have started harnessing that powerful thermal energy in the cold winter months.

From the ANR’s data, we find that estimated non-residential food scrap generation across the state totals around 2,500 tons per week. That’s 5 million pounds every week, or 260 million pounds every year. Of that total, about 13% of all estimated food scrap generation is from just two places: Cabot Creamery in Middlebury (288 tons/week), and West River Creamery in Londonderry (49 tons/week). Vermont sure loves cheese! When we remove these two outliers from our distribution, we get a slightly less skewed result, with the majority of non-residential facilities estimating less than one third of a ton of food waste per week.

What does this mean for our state meeting the 2020 goal of banning all food scraps from landfills? Well, since 2012, based off of the estimates we have and the benchmarks set by the law, we might have expected to see tonnage per week and total number of non-residential generators composting increasing by these amounts each year.

This reflects what we would expect, knowing that high-tonnage food scrap generators are few but large, and lower-tonnage generators are numerous. On a map, we can see food scrap generators that are currently required to compost under Act 148:

Come 2020, however, the number of food scrap generators (which will then include residential generators as well) will increase significantly.

Here is the same map as above, with the addition of the remaining non-residential food scrap generators that will be expected to compost their food scraps by that time:

If we isolate the new additions and aggregate them by locality, we can see from the hex-binned map below where we might expect an increased demand in food scrap collection:

(Note: Totals listed for each hex bin indicate total number of facilities that will be expected to compost by 2020 being added to those who are already composting in that area).

So, who is collecting all of these food scraps? Where do they go? The Agency of Natural Resources has created an interactive Materials Management Map, available here that allows local residents and business owners to connect with food shelves and food scrap waste facilities in the area. Additionally, there is a regularly updated directory of food scrap haulers across the state, with areas that they serve.

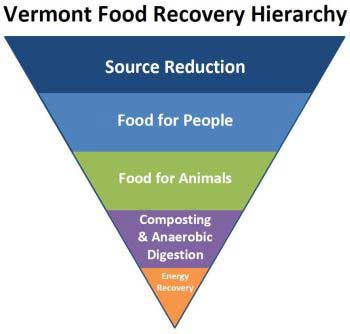

One important thing to note about Act 148 is that it’s not just about sorting waste: it’s also about conserving and diverting materials, so that less goes to waste overall. The Vermont Food Recovery Hierarchy, based off of the EPA’s guidelines for managing food waste, emphasizes that decreasing food waste starts with reducing overconsumption to begin with. Then, food that is still fit for human consumption should go to people.

I spoke with Natasha Duarte of the Composting Association of Vermont, and learned from her about Vermont’s “charity food system”. The Vermont Foodbank cites a statistic that “in Vermont, 1 in 4 people struggles with hunger”. According to Natasha, since the establishment of Act 148, the charity food system in Vermont has seen an estimated 40% increase in donations to food shelves. Salvation Farms is one such member of the charity food system here in Vermont. That organization provides job skills to workers, such as youth and prison inmates, who glean (rescue un-harvested produce) from farms across the state and deliver the food ‘seconds’ to local food shelves.

Image below from VPR: “Prison Labor Bringing Gleaned Crops To Food Shelves”.

The Vermont Farm-to-Plate Network Atlas allows users to find everything from food producers (farms) and consumers (restaurants, food shelves, businesses) to waste facilities, community gardens, and compost producers. Between that resource and the ANR’s Materials Management Map, it’s easy to see how informed Vermonters might get on track to meet the 2020 composting deadline. Check out those resources, as well as this map showing aggregate binning of non-residential food scrap generation alongside waste facilities and community gardens (enormous thanks to Libby Weiland at the Vermont Community Garden Network for sharing this data):

Meanwhile, here in Chittenden County, residents and business owners are stepping up and organizing ahead of the 2020 goal. I spoke with Cameron Scott and Jacob Wollman, who run No Waste Compost, a compost pickup service in the area. Their mission is “to make an affordable and responsible composting service for all of Vermont”. Their “smell of the month” videos are something of a hit among customers.

The No Waste folks bring their residential pickups over to Green Mountain Compost in Williston, which is a facility run by Chittenden Solid Waste District (CSWD). Haulers can drop off food scraps there for a ‘tipping fee’, which is determined by the weight of the waste dropped off.

Composting isn’t just for food scraps! Below, we see a recent deposit of leaf and lawn debris at Green Mountain Compost from a local landscaping company:

Green Mountain Compost offers composting advice and tours of their facility to the public. I learned a whole lot during my time at their “Edu Shed” and touring the facility. You can sign up to take a tour here.

Above: At the Green Mountain Compost “Edu-Shed”, where tours begin and we learn about why and how to compost. Below: Alyssa Borowske (left) of the Department of Environmental Conservation; Lauren Layn (center) of Green Mountain Compost; and me (right), excited about the future of Vermont’s compost ecosystem!

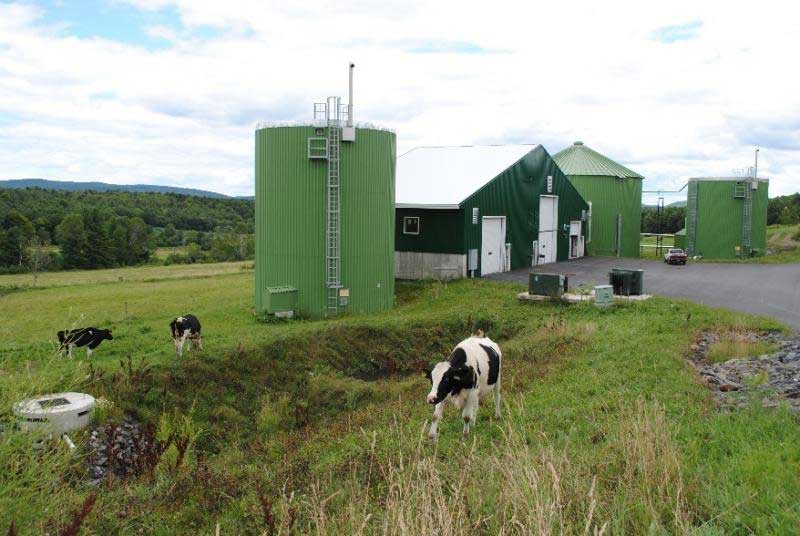

Another approach under consideration? Methane food digesters. Alex DePillis with the Vermont Department of Agriculture explains: “Taking food waste to digesters is a pathway we’re working on in Vermont. So far, we have one example: Pre-ground Norwich University cafeteria and catering waste plus brewery waste from Alchemist and others [was] combined [and], in a vacuum truck by Grow Compost, hauled to Vermont Technical College, who then spread the digestate (liquid agronomic nutrients from the digesters)”. Read more about “Big Bertha”, Vermont Tech’s anaerobic digester, here.

If you haven’t begun composting at home already, now is the time to start! Haulers across the state are increasingly accepting food scraps and yard debris from residences, or you can look locally for a community garden where you can contribute to the production of that ‘black gold’ compost that makes our farmed food so delicious!

Many thanks to the awesome folks at these organizations for teaching me more about Vermont’s compost ecosystem:

especially to Lauren Layn at Green Mountain Compost, Natasha Duarte at Compost Association of Vermont, Alex DePillis at Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Emma Stuhl at the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources, Libby Weiland of the Vermont Community Garden Network, and Cam Scott and Jake Wollman of No Waste Compost.

Further resources: Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation Vermont Agency of Natural Resources Vermont Agency of Agriculture Food & Markets Vermont Farm-to-Plate Network Vermont Community Garden Network Vermont Foodbank Hunger Free Vermont