Stories help us encode and understand our collective existence, underpin cultures, and help frame the possible. Describing the ecology of all human stories is an essential scientific enterprise. With the advent of the internet and massive digitization this vital work has become, in part, a data-driven one.

There are many aspects of stories to characterize and here we take on just one: The overall emotional trajectory.

In a lecture recorded in 1985, Kurt Vonnegut introduced the idea of quantifying the emotional arcs of stories. He suggested that “Man-in-a-hole” is a primary kind of shape in the dimension of good-ill fortune. “Somebody gets into trouble… gets out of it again. People LOVE that story!” If you haven’t seen the video, it’s less than 5 minutes long and a rewarding experience:

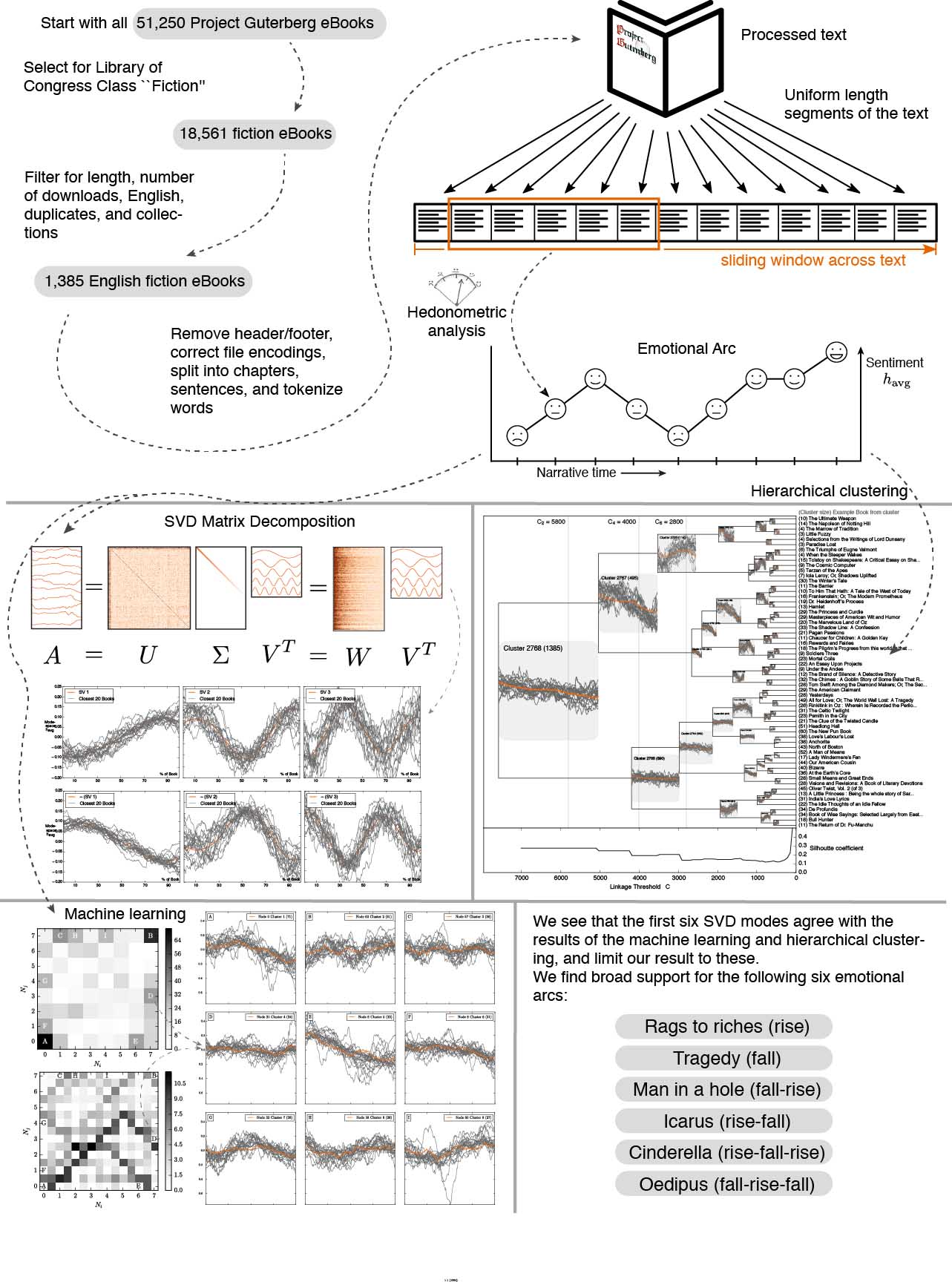

Vonnegut pointed out that computers would be perfectly suited to the task of finding good-ill fortune trajectories, and with this inspiration and today’s computing power, we tested his instincts on a large supply of books. We extracted and analyzed the emotional arcs of 1,722 novels from the Project Gutenberg corpus using sentiment analysis, and found six common shapes:

- Rags-to-riches,

- Tragedy,

- Man-in-a-hole (see below for more),

- Icarus,

- Cindarella,

- Oedipus.

Here’s a graphical overview of our process:

It seems that in the space of all possible emotional arcs, we tend to prefer a handful of comprehensible building block shapes.

We have interactive visualizations of the emotional arcs of thousands of books (and movies) at hedonometer.org. Details can be found in the publication in EPJ Data Science, the paper’s online appendices.

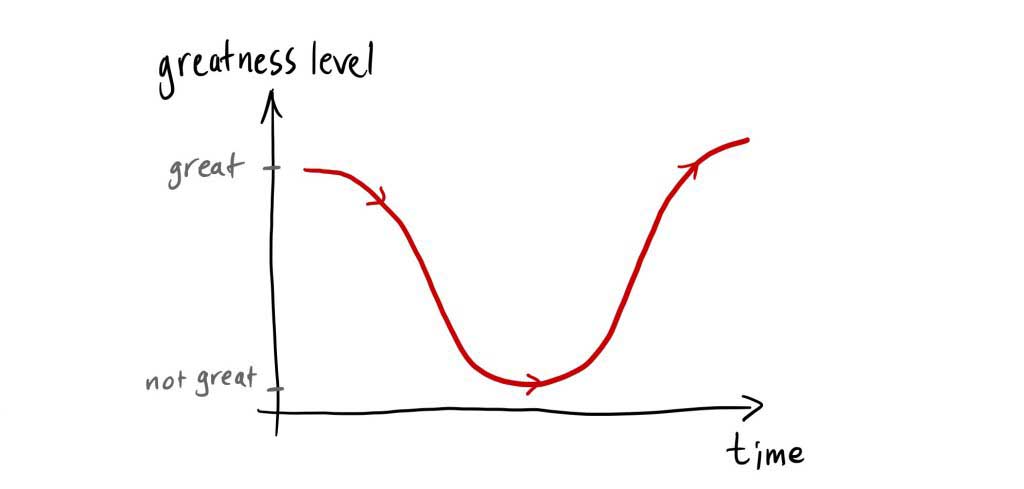

One more thing: Tomorrow is the 2016 US Presidential Election. Slogans are, when done well, powerful indicators of a larger narrative. The slogan “Make America Great Again”, first used in Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign (and at times by other politicians including Bill Clinton), induces a remarkably full dynamic that matches Vonnegut’s Man-in-a-hole trajectory. In fact, it’s a much stronger framing as Man-in-a-hole does not suggest a trajectory through time by itself (The Metamorphosis would roughly fit for example though the “hole” changes in nature). In four words, “Make America Great Again” manages to indicate a perceived state of the past and present, and a desired future:

Our stance here is apolitical—we are attempting to analyze stories scientifically, and we saw that “Make America Great Again” fits one of Vonnegut’s basic shapes.

And our work on emotional arcs is just one part of understanding the ecology of stories. There is much more to do: Extracting and comparing plots, character paths, comparing across cultures and time periods. But all this now seems possible.