On January 21st, 2017, the Women’s March on Washington gathered enormous crowds in collective protest of the newly inaugurated President of the United States, Donald Trump. Meanwhile on Twitter, people used the hashtag #WomensMarch to magnify and respond to the on-the-ground movement.

Here at the Computational Story Lab, we found ourselves wondering about a few things. How many people were involved and how many tweets did they produce? What were the most popular #WomensMarch tweets? What adjacent topics were people discussing? To try to answer these questions, we analyzed over 850,000 tweets posted on January 21st discussing the Women’s March on Washington. The numerical IDs of these tweets, along with the code used to generate the results and figures in this blog post, are available on GitHub.

Tweeting the Women’s Marches

Crowd scientists and other statistical professionals estimate that nearly 470,000 people marched on Washington, and that about 3.2 million people in total marched at over 300 sites across the United States. An equally voluminous number of people tweeted about the marches on the day following the presidential inauguration.

Chris Fusting (a fellow conspirator of mine in applied mathematics) and I searched for tweets containing mentions of “Women’s March” or #WomensMarch. From Twitter’s Decahose, a 10% sample of all public status updates, we extracted 854,811 tweets pertaining to the various Women’s Marches.

The tweets were posted by 527,988 unique users, resulting in an average of approximately 1.6 tweets per user. About 86% of those tweets were retweets, which is standard in most samples of Twitter. Scaling appropriately (because our sample was 10% of the whole), there were an estimated 8.5 million tweets from 7.3 million unique users. This is likely an underestimate of the true number of tweets and users on January 21st, due to the fact that most replies to tweets in our data set are probably not in our data set. Many people may not explicitly mention “Women’s March” in a reply to a tweet about the Women’s March, and there is no easy way to use the Twitter API to collect the replies to the tweets.

Estimated number of tweets pertaining to the Women’s March on January 21st, 2017. Time is Eastern Standard Time. Estimates come from a rescaling of a 10% sample of Twitter data from that day.

In the above figure, we see that the number of tweets about the Women’s March steadily grew throughout the day, peaking in the mid-afternoon. In the roughly 2 hour peak of tweeting, almost 2 million tweets were generated, about 22% of the tweets from the entire day. While the number of tweets tapered off following the official ends of the marches, people were still writing about 83 tweets per second around midnight.

With an estimated 120,000 retweets, Randi Mayem Singer had the most popular tweet on the day of the marches.

It’s OFFICIAL #WomensMarchOnWashington is biggest inaugural protest in HISTORY. Sorry Mr. Trump, THIS is what a populist movement looks like pic.twitter.com/mREzlQnUAy

— Randi Mayem Singer (@rmayemsinger) January 21, 2017

She was followed by Parks and Rec icon Ron Swanson, a.k.a. Nick Offerman, who had a tweet that picked up about 110,000 retweets.

I’m a nasty girl #WomensMarch pic.twitter.com/GjFriucGUY

— Nick Offerman (@Nick_Offerman) January 21, 2017

The third most popular retweet was from Hillary Clinton, whose tweet depicted three of the major organizers of the Women’s March on Washington.

‘Hope Not Fear’ Indeed. And what a beautiful piece by Louisa Cannell. #womensmarch pic.twitter.com/7h3Bzx79nB

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) January 21, 2017

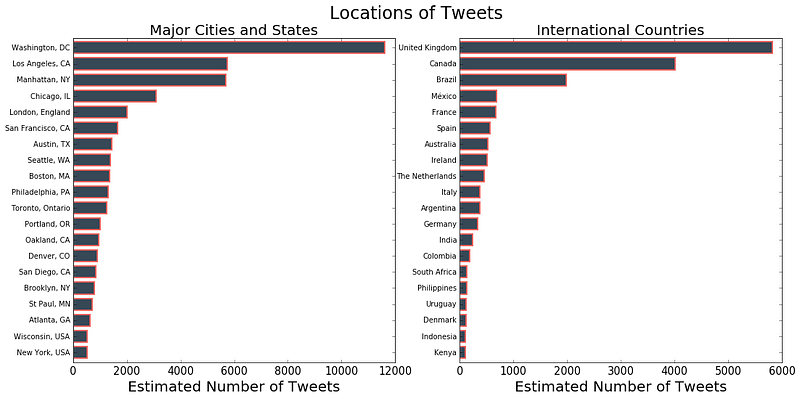

Tweets came from all over the United States, as other cities held their own Women’s March. The five major locations for tweets were Washington, Manhattan, Los Angeles, Chicago, and, perhaps surprisingly, London. Reflecting a strong international interest in the Women’s March on Washington, we also saw tweets originating in Canada, Brazil, France, Australia, and other countries.

Number of tweets from locations both within the US and across the globe. Estimates come from a rescaling of a 10% sample of Twitter data from that day. Estimates are significantly lower than one may initially expect because only 1–3% of all tweets are tagged with geo data.

Networks of Conversation around #WomensMarch

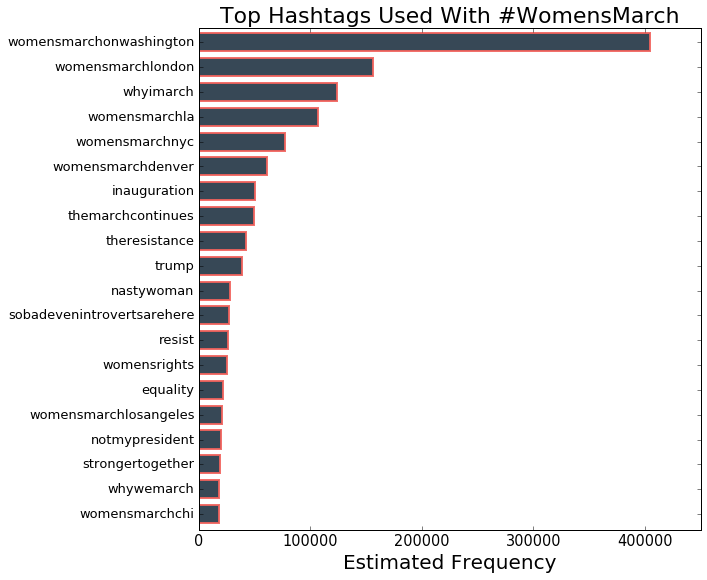

There are many advanced natural language processing and machine learning tools we could apply to get a sense of the texture of the #WomensMarch conversations. Here, we simply look at the most popular hashtags, since they act as good indicators of the broader topics.

The most popular hashtags used in Women’s March tweets. The hashtag #WomensMarch has been excluded since it was (obviously) the most popular hashtag on January 21st.

The hashtags reinforce the solidarity of other cities with the Women’s March on Washington. As with the tweet locations, we see references to marches in Los Angeles, New York City, Denver, and Chicago. We found that #WomensMarchLondon was the second most popular hashtag after #WomensMarchOnWashington. Some hashtags carried more than the flat declaration of the march such as purpose, subversion, and comedy conveyed in #WhyIMarch, #NastyWoman, and #SoBadEvenIntrovertsAreHere.

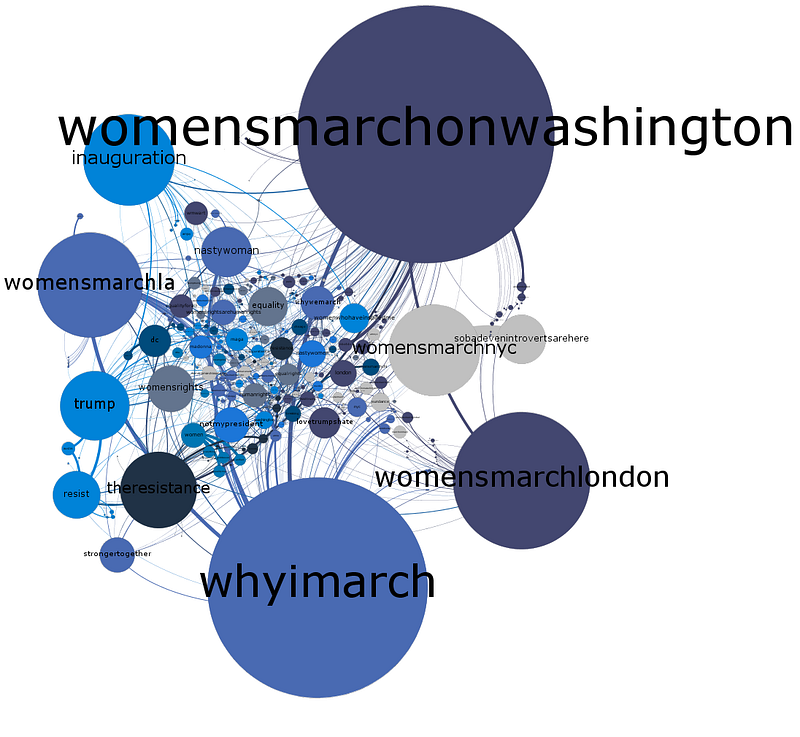

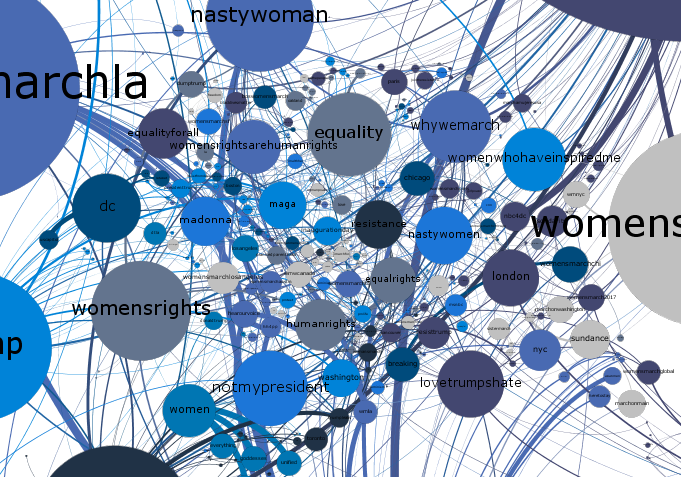

We can gain a better sense of the larger web of conversation by examining a network of hashtags where we simply connect two hashtags if they appear together in the same tweet. For the day of the march, we find a network of 14,500 hashtags with 58,000 connections between them. It's helpful to filter this network down to its most important aspects, so we chose to apply the disparity filter, a technique for extracting the backbone of a weighted network. We’re now left with 407 of the most important hashtags and 776 links between them. This network is pictured below.

Topic network of Women’s March hashtags. Node sizes are proportional to the number of times the hashtag was used. This network is the result of applying the disparity filter to extract the multiscale backbone of the full hashtag network. The hashtag #WomensMarch has been excluded from construction of the network, as it appears in nearly every tweet.

Topic network of Women’s March hashtags. Node sizes are proportional to the number of times the hashtag was used. This network is the result of applying the disparity filter to extract the multiscale backbone of the full hashtag network. The hashtag #WomensMarch has been excluded from construction of the network, as it appears in nearly every tweet.

Not surprisingly, #WomensMarchOnWashington is the most popular hashtag in the core of the network. However, this view of the hashtags gives us a different perspective on the topics of conversation surrounding #WomensMarch. For instance, in the bottom left we see a cluster of anti-POTUS hashtags (#Trump, #TheResistance, #Resist, #StrongerTogether), which were not immediately apparent when just viewing the most popular hashtags. We also see that #SoBadEvenIntrovertsAreHere is heavily connected to #WomensMarchNYC, suggesting it originated from users in New York.

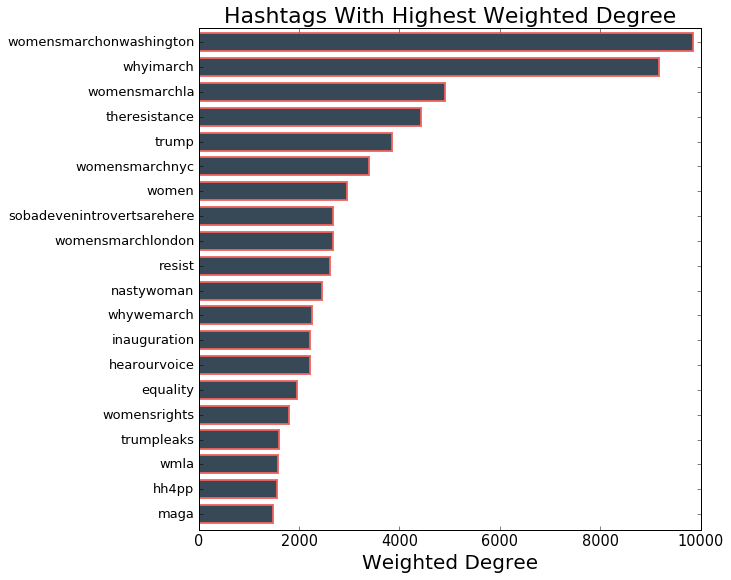

The hashtag topic network gives us alternative ways to rank the importance of these hashtags. Rather than ranking just by how popular a hashtag was, we can rank by how well a hashtag does at connecting to other hashtags. That is, we can look at its weighted degree: the number of hashtags it appears with, weighted by the number of times it appears with each hashtag.

We see similar hashtags as to when we ranked just by popularity, but the magnitudes are quite different now. Here #WhyIMarch is nearly as “important” as #WomensMarchOnWashington in terms of how well-connected it is, while #WomensMarchLondon has fallen significantly in ranking. Meanwhile, new hashtags have entered the rankings, such as #HearOurVoice and #MAGA, indicating that these hashtags may not have been particularly popular, but they are more central to maintaining the structure of the topic network.

This touches on a much broader concept of network centrality, and there are far more nuanced ways of measuring the most topologically key parts of a network.

Through analysis of more than 850,000 tweets, we have gained a (peculiar) bird’s eye view of the online conversation surrounding the Women’s March on Washington. We have formulated this view largely from simple count data and the construction of a hashtag topic network. Through the hashtag topic network, we see there is a complex web of solidarity, resistance, and support underlying the #WomensMarch conversations.

What more could we look at?

- We’ve gained some sense of how many people were tweeting, but who were those people? FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver discussed how physical turnout for the marches was driven by Clinton supporters. Is it the same story for those not at the marches but still tweeting about them?

- Hashtags can be good indicators of topics, but there is an abundance of language beyond the hashtags. Further textual analysis could apply topic modeling to understand the topics from a broader angle, or sentiment analysis to understand the online emotional dynamics during the day.

- Given the outcome of the election, there are certainly people who did not agree with the Women’s March. What were those people saying? How did they interact with #WomensMarch tweeters? Did any counter-protest coalition form specifically in response to the Women’s March?

If you would like your hand at answering any of these questions, the tweet IDs and code underlying this post are available on GitHub.