There is an overwhelming consensus among scientists that anthropogenic climate change is real. However, politicians often benefit from disagreeing with this consensus, and media coverage tends to confuse the general public.

With a myriad of different ideas, opinions, and sentiments surrounding this controversial topic, we were curious, what does Twitter think about climate change? Does the Twittersphere agree with scientists? With the sentiment analysis hedonometer instrument at our disposal, we analyzed a random 10% of tweets containing the word “climate” from September 14, 2008 through July 14, 2014.

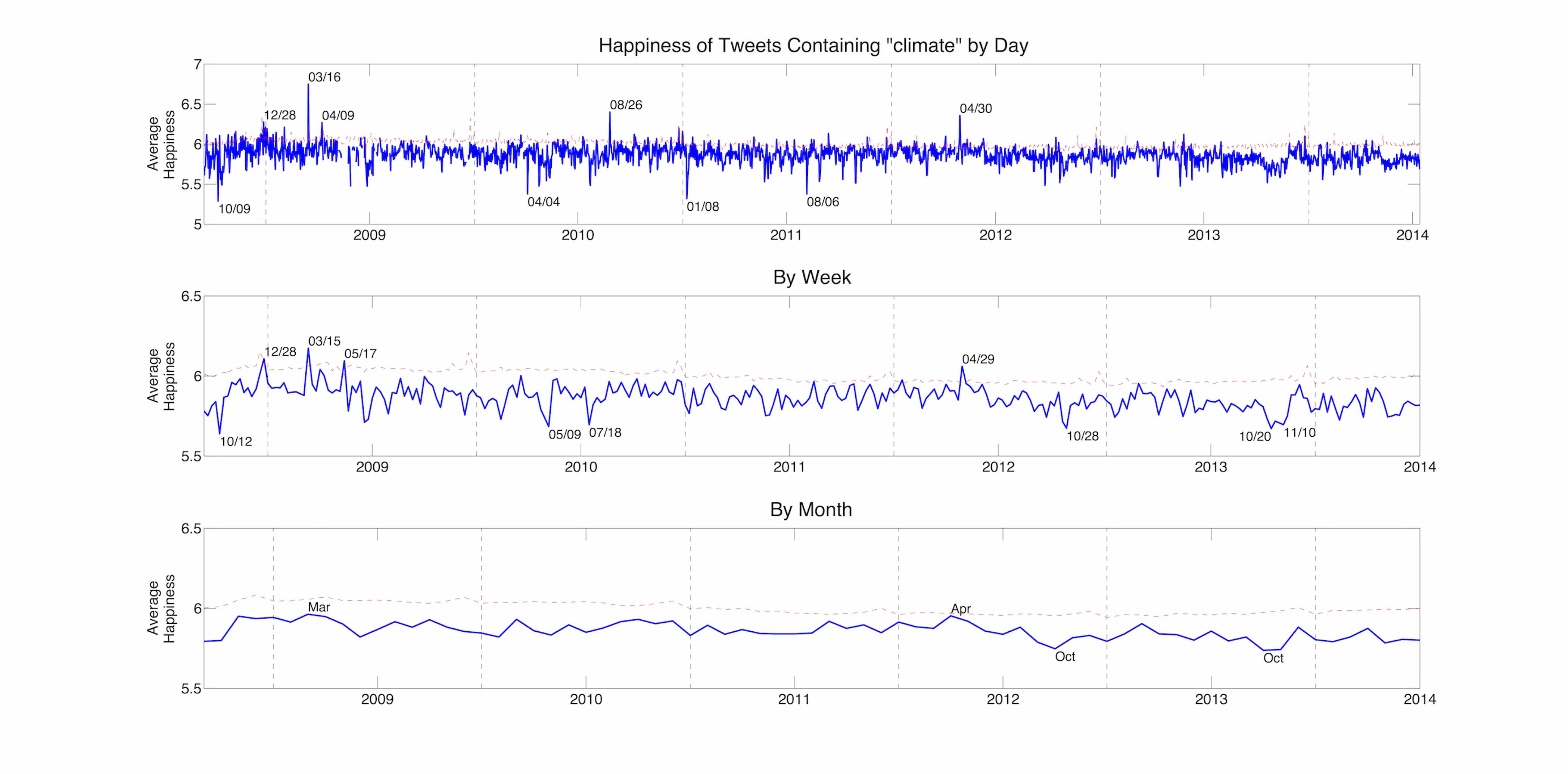

Whether you are a denier or an activist, it may not be surprising to learn that in general, tweets containing “climate” are less happy than the background from which they are drawn. The average happiness plots below demonstrate that the happiness of climate tweets over the study period (blue lines) is typically below the happiness of unfiltered tweets (dotted red lines), regardless of time scale resolution.

Average happiness of tweets containing “climate” from September 2008 to July 2014 by day (top), by week (middle), and by month (bottom). The average happiness of all tweets during the same time period is shown with a dotted red line.

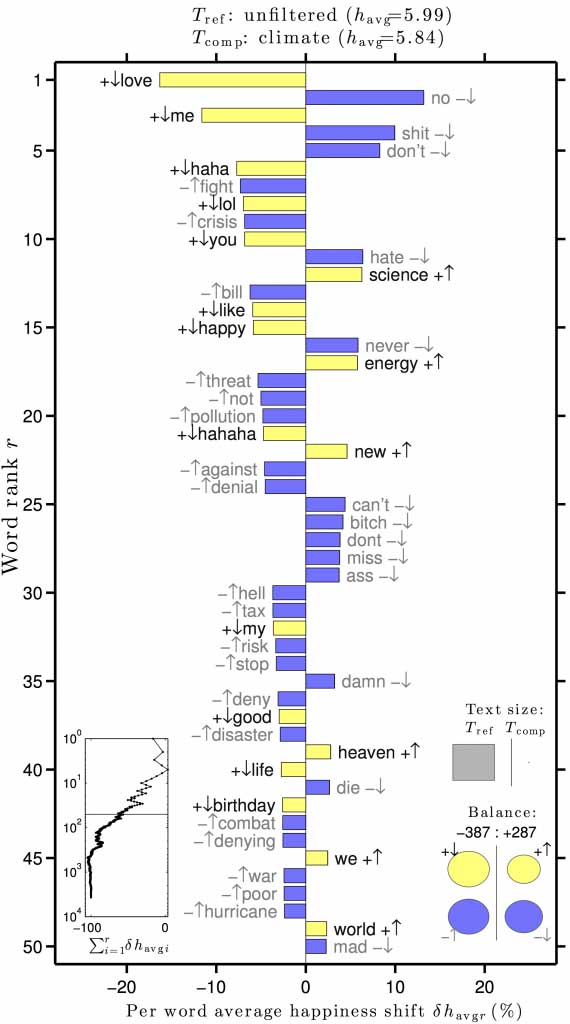

To identify the specific words causing the decrease in happiness, we generate our handy-dandy word shift graph for tweets containing “climate” versus unfiltered tweets. We see words leading us to believe that most Twitter users consider climate change to be a “fight”, “crisis”, and “threat”. The words in this graph heavily lean towards the climate activist side (“science”, “energy”, “disaster”, “combat”), however this isn’t to say that climate deniers do not use Twitter.

A word shift graph comparing the happiness of tweets containing the word “climate” to unfiltered tweets. The reference text is roughly 100 billion tweets from September 2008 to July 2014 (around 10% of tweets produced during this time frame). The comparison text is a compilation of the subset of tweets containing “climate” from the same time period.

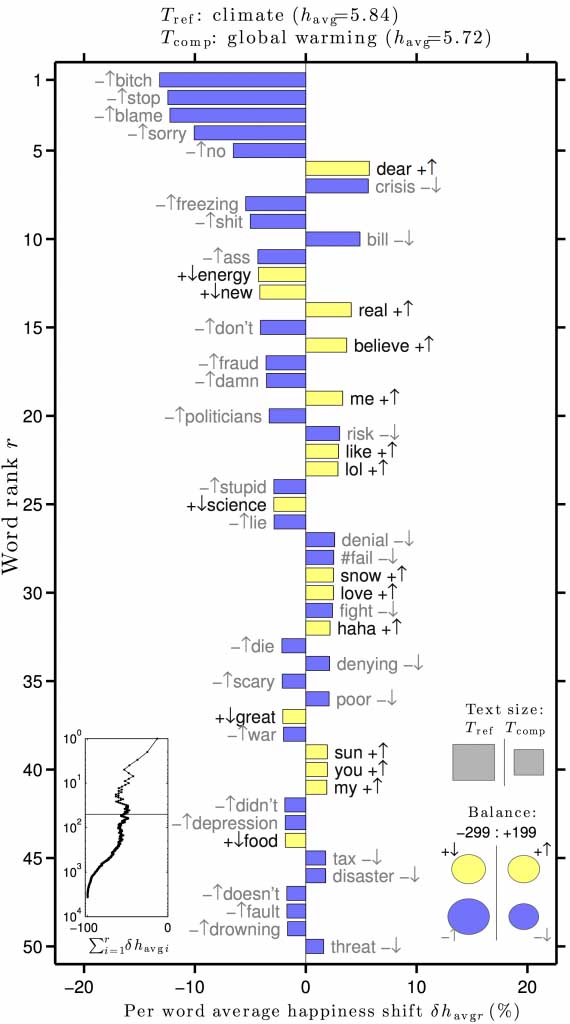

Through some further research into other climate change related keywords, we discovered that climate change activists and deniers are both present on Twitter, however they tend to use different terminology. In comparing tweets containing “climate” to tweets containing “global warming” we discover that “global warming” is used more by climate change deniers (“stop”, “blame”, “fraud”). It seems that it is easier to deny “warming” than it is to deny “change”. In fact, “#globalwarming” is often used sarcastically in tweets referencing cold weather (“freezing”, “christmas”, “december”), e.g. ‘Oh it’s negative ten degrees in Burlington, Vermont today #globalwarming’.

A word shift graph comparing tweets containing the word “climate” to tweets containing the phrase “global warming”.

Our research demonstrates that Twitter may be a valuable source for the spread of climate change awareness. Twitter represents another portal though which the general public can learn new information and form their own thoughts and opinions on matters such as climate change.

For more, we invite you to read our full, open access analysis which appeared in August 2015 in PLoS ONE:

“Climate Change Sentiment on Twitter: An Unsolicited Public Opinion Poll.”

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0136092

Emily M. Cody, Andrew J. Reagan, Lewis Mitchell, Peter Sheridan Dodds, and Christopher M. Danforth

PLoS ONE 10(8): e0136092; 2015.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136092